Click subject below for report ▼

ANIMALS

with

Paul Reeves

BIRD BOX

with

Paul Reeves

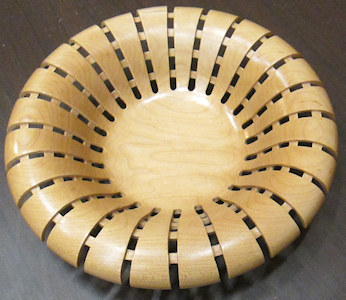

BOWL

from a PLANK

with

Paul Reeves

BOWL TURNING TECHNIQUES

with

Paul Reeves

BOX of CONTRASTING WOODS

with Paul Reeves

BUTTONS

with Paul Reeves

CLOCKS in WOOD

with

Andy Ogilvie

COLOURING with a SPLASH

with Paul Reeves

GAVEL

with Paul Reeves

HANDLES & FEET

with Graham Turner

JEWELLERY with

Andy Ogilvie

and Paul Reeves

KILNER JARS

with

Andy Ogilvie

KITCHEN ITEMS

with

Paul Reeves

LIGHT BULBS in wood

with

Paul Reeves

MIXED SOLID MEDIA with

Andy

Ogilvie

MULTIPLE CENTRES TURNING

with

Paul Reeves

MUSHROOMS DECORATED

with

Paul Reeves

OFF-CENTRE

TURNING

with

Paul Reeves

OFF-SET BOWLS

with

Paul Reeves

PENCIL

SHOOTER

with

Paul Reeves

PLATES &

PLATTERS

with

Paul Reeves

PLYWOOD

with

Ed Walker

PODLETS

with

John Bolt

PUZZLES & TRICKS

with

Paul Reeves

SPHERE TURNING

with Paul Reeves

SPINDLE & FACE PLATE TURNED

with

Paul Reeves

SPINDLE revision

with

Paul Reeves

STRAIGHT

from the TOOL

with

Paul Reeves

STREPTOHEDRONS

with

Andy Ogilvie

THREAD CUTTING SCREW BOX & TAP

with

Paul Reeves

THREE POINT

BOWL

with Andy Ogilvie

TEXTURING

with

Paul Reeves

THREE LEGGED STOOL

with

Paul Reeves

TOOTHPICK HOLDER with

Paul Reeves

TOY CAR RACING

with

Andy Ogilvie

TREEN HAND-HELD MIRROR

with

Paul Reeves

TWO-PART STICK/LAMP + ADDED VALUE

with

Paul Reeves

UNNATURAL NATURAL EDGE

with

Paul Reeves

WOODEN WHISTLE

with

Paul Reeves

Click subject above for report ▲

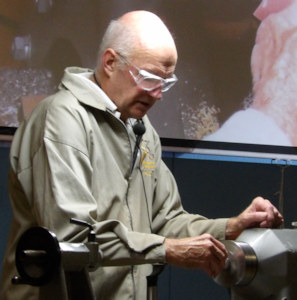

Clocks

in

Wood

with

Andy Ogilvie

Thu 20th February 2025 at MWCC Club Night

Traditionally in horology, the term 'clock' was used for an instrument that sounded regular time periods, while one that didn't strike audibly was referred to as a 'timepiece', thus doing as it says and tells the time "peacefully".

Obviously the clock mechanism is

beyond the capabilities of the majority of us but the regular wood turning

Suppliers of accessories, plus the likes of eBay & Amazon ensure they are readily &

speedily available.

There are two basic mechanisms - Clock Movement, which come as an

enclosed mechanism fixed into the back of a clock face with a choice of shaft

lengths protruding

through to drive a choice of hands; all for typically <£10

(circa 2025)

and Clock Insert, which are self contained working timepieces for typically

around £10 - £15 (circa 2025).

Below are some examples with added details like bullet cases or slotted brass

screws with slots aligned as hour markers.

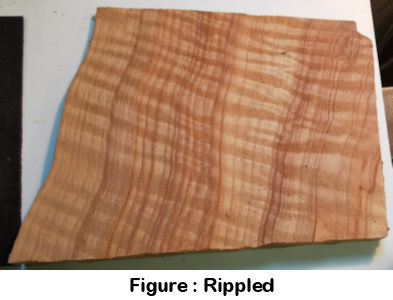

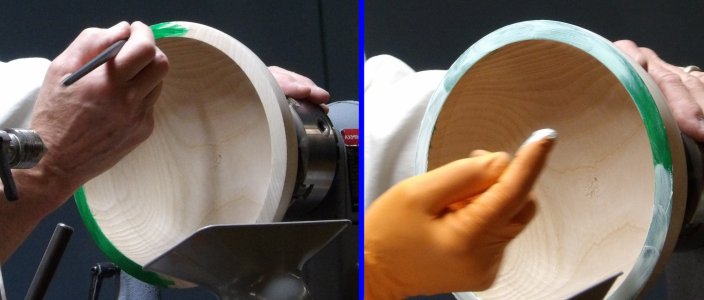

Tonight's design is a Timepiece with the Movement option to a platter-size blank of wood with expected interesting ripple and figure. The plan was to first work on its back to accommodate a recess for the mechanism, shape the rest then reverse the piece and deal with the front face which is of course what is in view most of the time.

Because a foot or screw holes would impair the finished

work, the blank had been prepared by being stuck onto a MDF Face Plate,

mysteriously using

a line of hot glue around the edge of where the rim touched the MDF.

Normally, half a dozen blobs of glue from a hot glue gun would suffice.

Top Tip

: Use clear polyethylene sticks (aka polythene) as they will

release the blank when heated with hot air from a hair dryer; other glue sticks

tend to bond

the MDF to all your hard work!

The blank had been turned to the round and a 8mm hole drilled dead centre for

the shaft driving the hands. This blank had some protective wax around its edges

so in case this reduced the effectiveness of the glue, Andy elected to use a nut

& bolt through the centre hole for assured security as a kind of 'bolt & braces'

precaution.

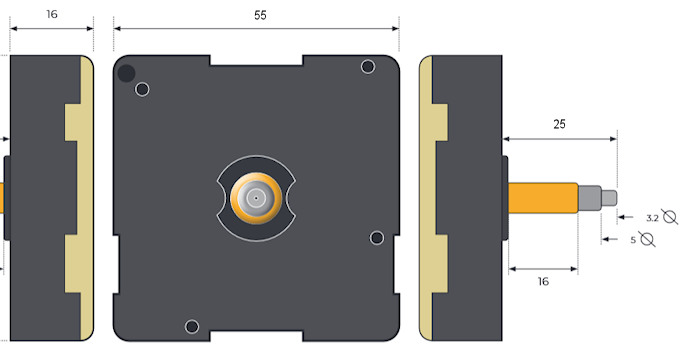

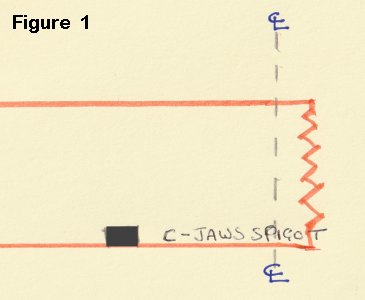

Each supplier of Movements invariably have different dimensions; Andy's example had the

following :-

Having trued off the central section

of the back face, Andy wanted to turn a hole deep enough for the movement to fit

flush so that the timepiece would lie flat against the wall. The depth of the

Movement was 16mm (some kits may also have a rubber washer and thickness of

Clock Hangar to consider).

He found the correct radius to use by measuring the diagonal of the movement

case and dividing by two. He also had to consider room for the

shaft to extend through the front face sufficiently to allow the retaining nut

to have enough threads to fasten tight.

So

in his case, he needed the recess to be at least 16mm deep to ensure the

Movement didn't protrude out of the back and as the threaded extension is 16mm

(the 4mm thick nut can be countersunk into the face) the bottom also

needed to be at most 16mm from the front face. His trimmed blank was now 30mm

thick so the depth of the recess would have needed to be at least 14mm deep

for the hands to be clear of the face, thus a recess of 16 to 17mm satisfies both

requirements.

If your blank doesn't have enough depth for the movement to become flush with

the back face, you should find your Clock Mechanism includes a Clock Hanger

accessory for hooks which will resolve the problem.

Ordinarily, one could create the round hole at this stage. However, as Andy was using a nut & bolt through the centre hole as extra security, he elected to delay creating the recess for the movement until he had finished the shaping and could then safely remove the nut & bolt. One could mark in the calculated diameter using a set of dividers.

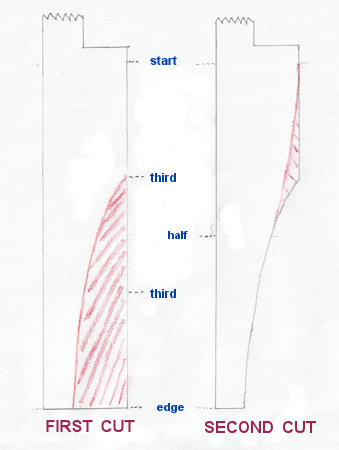

Ogee

Shaping

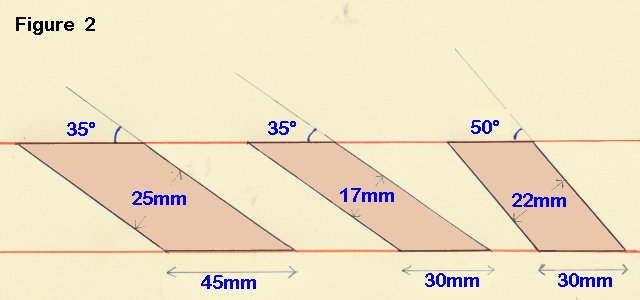

Andy wanted to give the piece some finesse and style rather than leave it as a

cylindrical block so opted to create an Ogee shape by a method advocated by

professional turner, Jimmy Clewes, (a Geordie but now operating

out of Western USA).

He

decided where the shape was going to start and then divided the distance to the

edge into thirds. The thickness of this blank was now 30mm, so Andy decided that

a finished edge thickness of about 12mm would look in proportion.

He

decided where the shape was going to start and then divided the distance to the

edge into thirds. The thickness of this blank was now 30mm, so Andy decided that

a finished edge thickness of about 12mm would look in proportion.

Working with just the outer two-thirds of the piece, his first cut was to turn

away a semi-parabolic shaped curve finishing at the 12mm mark at the outer edge.

He marked on this newly produced curve exactly halfway between the start and the

edge and for his second cut, carefully turned away the inner third section so

that the finished curve swept smoothly from the start to the halfway point.

With the shaping completed, Andy started to create the recess with a Parting Tool cutting from the earlier circular divider mark. Eventually he needed to remove the nut & bolt to finish the rest of the centre down to a level 18mm depth with the aid of a Box Cutter.

The back surface was sanded down to about 320 grit; a coat of Sanding Sealer was applied and allowed to dry before going over the sealed surface with the same 320 grit with a light touch before continuing with 400 grit. He applied some Chestnut Cut 'n Polish with the lathe stopped, then switched on the lathe and buffed to a shine whilst smoothing the timber at the same time. It dries almost immediately and can be over-coated with Friction Polish or wax for a higher shine.

Microcrystalline Wax

This type of wax has different methods of application

dependent upon

manufacturer. All of them have a melting point higher than

normal body temperature which helps to avoid finger marks,

but

Renaissance© Wax uses a precise proportion of

White Spirit which dissipates quickly and is best applied to the cool surface of

small areas at a time, which can then be buffed without waiting,

whereas :

other

microcrystalline waxes, eg Chestnut©

use alternative solvents that need about 20 minutes to dissipate to allow their

wax to form a dense coat. Because their constituents will dull while the solvent evaporates,

one needs to allow sufficient time for the solvent to disperse before

buffing.

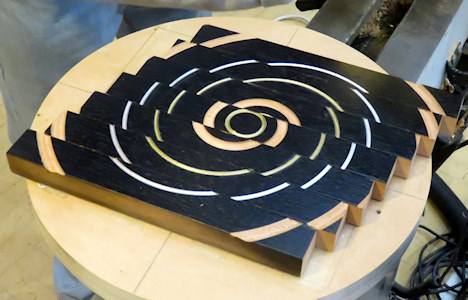

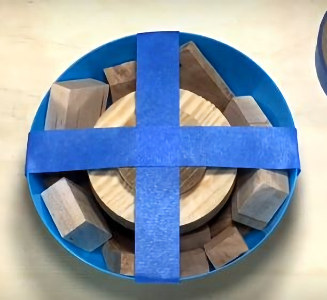

In order to work on the front face, Andy removed the piece from the faceplate using decorator's scraper and a mallet without the need of hot air. The mystery of his gluing method was revealed with the surprise that it had already been prepared as a multi-coloured resin face with hour graduations created by drawing contrasting colours out from the centre prior to it setting hard. This explains his method of gluing just the edge earlier in his demonstration because the resin surface was lower than the rim and wouldn't be in contact with the MDF.

His

plan had been to have concentric circles of resin with Black in the middle, Green,

Purple, Blue and then Gold in the outside ring, using a frame (pictured

right). He had also prepared a paper

template with 12 hourly graduations placed underneath the timepiece in

preparation for when the frame was lifted away and a lollipop stick could be

dragged from the centre to the hour mark.

His

plan had been to have concentric circles of resin with Black in the middle, Green,

Purple, Blue and then Gold in the outside ring, using a frame (pictured

right). He had also prepared a paper

template with 12 hourly graduations placed underneath the timepiece in

preparation for when the frame was lifted away and a lollipop stick could be

dragged from the centre to the hour mark.

Unfortunately, this didn't work exactly as he had hoped but thought he would

highlight some errors of judgement for anyone who wished to try similar

themselves and get a better result.

The procedure took place on a bitterly cold day so Andy had abandoned his chilly garage workplace in favour of a warm Utility Room and warmed up his resins in hot water to ensure thorough mixing of resin, hardener & tint. This subsequently resulted in the resin mix being thinner & runnier than usual, which was more prone to creep under the dividers in the frame and more readily to mix/float/sink with its neighbouring colour when removing the frame. He also acknowledged that he needed to have left the mix to harden more before dragging the lollipop stick edge to form the graduations.

With the piece mounted by jaw expansion

onto the walls of the recess created for the movement, he

finished off the centre by providing a countersunk space for the thin retaining

nut so that it allowed the shaft to extend precisely

without the hands impeding the face, trued off all the high points and matched the rim edge

with the centre decorative detail.

The wooden parts of the face were sanded, and sanding sealer applied.

While dealing with the resin, it was important to go steadily through

considerably finer grits using all the intermediary grades with an increasingly

lighter touch to obtain an absolutely smooth surface. Alternative final

compounds could be cutting paste or even metal polish. The wood was finished

with Renaissance Wax.

There was now a choice of hanging

the Timepiece.

Andy had planned to have it flat against the wall, so he created a short upward

hole with a 8mm drill at the very top (in line with the 12 mark) of the flat

back above the Movement recess large enough for a picture hook to engage.

The alternative is to fit the aforementioned Clock Hanger.

(photos by Andy Ogilvie, Rick

Patrick & Paul Reeves)

<

Pencil

Shooter

with

Paul Reeves

Thu 16th January 2025 at MWCC Club Night

The forceful characteristic needed to

propel a pencil is stretchiness, which can be obtained from elastic bands or springs.

The majority of online examples rely upon sawn shapes to provide strength for

supporting the stress & forces involved with taut rubber bands but as

Woodturners, we want predominantly turned components.

For this demonstration, Paul had chosen to use the energy provided from

releasing a compressed spring to fire a hexagonal pencil (doesn't

have to be a Reeves

pencil of course!) that is no larger than 8mm diameter.

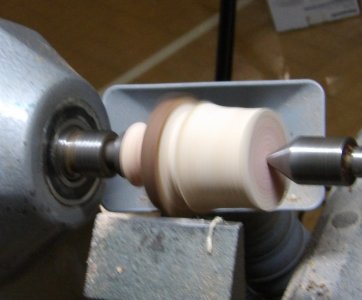

The 'weapon' shown below comprises of a Barrel with 2 bore sizes to accommodate

the 8mm pencil through the Muzzle end and 18mm bore through the Breech end. The

firing mechanism is a combination of Piston (with a notch for a trigger), the

Spring and a Rod through the Breech Cap to the Knob, which holds everything together.

Barrel

Paul decided to enlarge the first

10mm or so of the Barrel so that the Spring/Piston mechanism would clear all

threads whenever inserted or removed; this only needed the

Bore to be increased about 2 or 3mm with a Box Cutter.

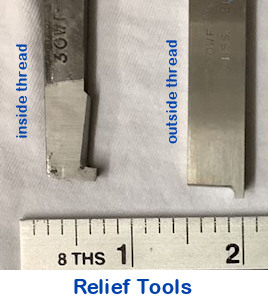

Next, a Relief Tool was used to

create a slot into the wall of the Barrel next to the step of the 18mm Bore

width. The thread is created with the Thread Chaser when it 'lands' and is

'taken off' in a smooth circular motion. That slot will allow freedom for the

Chaser to lift clear of the inside threads before it gets stopped suddenly

against the step down of width and would damage the threads already made.

Next, a Relief Tool was used to

create a slot into the wall of the Barrel next to the step of the 18mm Bore

width. The thread is created with the Thread Chaser when it 'lands' and is

'taken off' in a smooth circular motion. That slot will allow freedom for the

Chaser to lift clear of the inside threads before it gets stopped suddenly

against the step down of width and would damage the threads already made.

Beech doesn't often take a thread as well as some closer grain woods but in this

demonstration, a perfectly good thread was obtained with just half a dozen

passes without having to resort to wily ploys like stabilizing the wood grain

with thin superglue. The thread and bore were checked and any roughness

was dealt with by brush or abrasives.

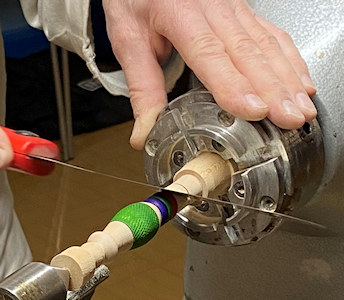

The piece was reversed in the chuck

to expose the Muzzle end and aided by the tailstock, lined up for the Jacob's

Chuck (now fitted with a sharp 8.5mm drill bit) to drill its hole down the

centre. As previously, start drilling slowly before speeding up, watch for

clogging up and clear out frequently until certain that you have drilled through

to the 18mm bored hole.

Paul then used a countersink in the Jacobs to create a chamfer in the Muzzle

Bore. This will help later when the Breech Cap is completed and screwed on such

that the Barrel can be held between centres. Again, to reduce friction, this end

of the Bore was 'polished' using a drill bit in a powered drill.

Breech Cap

The oversize start permits a thread to be

established and then by trimming the thread tips away, there is enough for the

Chaser to easily engage and re-cut the threads which will eventually reduce the

diameter to fit the female thread in the Breech Bore.

The oversize start permits a thread to be

established and then by trimming the thread tips away, there is enough for the

Chaser to easily engage and re-cut the threads which will eventually reduce the

diameter to fit the female thread in the Breech Bore.

Knob

Piston

Shaping the Barrel

Assembling

Rules for this Competition :-

● The piece will be judged on it's aesthetic appearance;

● It must be capable of propelling the provided pencil;

● The Club will provide 8mm hexagonal pencils with a rubber one end &

blunt the other;

● Powered by Spring/Elastic/Bungee/Compressed Air etc; (Chemical reactions

prohibited!)

● No restriction on size of Shooter.

● The Shoot-Off will be an entirely separate Target Competition from

a table top and its

Rules will be explained on the Night.

The January 2025 Competition was set to create a Pencil Shooter(s) of predominantly turned components that can propel a pencil.

(photos by Andy Ogilvie, Rick

Patrick & Paul Reeves)

<to

index>

Like most musical instruments made for children, the general

consensus is that despite being fun to make, it is wiser to make them for other

people's children and then, only to be presented as they are about to leave your

home!

This wooden whistle design is taken from 'Small Woodturning Projects' by Bonnie

Kline of the American Association of Woodturners which is aimed at improving

woodturning skills. One needs 2 blanks - one for the Barrel and a smaller piece

to create the 'Windway' from the Mouthpiece to the inner Bore. One could use

prepared wooden dowels although their quality these days are probably not as

good as something you could turn yourself out of a wood to match the Barrel.

The inside face of the Windway at the Bore end must have a clean & absolutely square edge - the

Exact measurements of length of Mouthpiece, Bore

Notch etc are not critical but a reasonable proportion would have both the first

section (Mouthpiece) and the second (Bore Notch) of about 15mm each. Paul marked

these on the cylinder together with about 10mm for a sphere at the end next to

the tail stock support in order

to gauge a shape for an ogee and any other decorative shapes he wanted in

between.

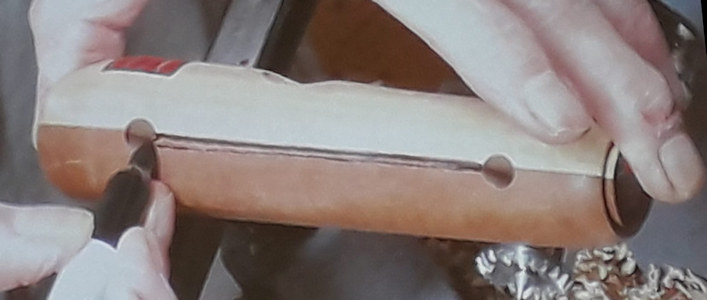

Using a Skew Chisel in combination with a Wire at the planned divisions, he cut

and burnt decorative lines of equal width & colour where marked. He used a 'wriggle' action with his ¼" Parting Tool to reduce cylindrical

areas to required

diameters and

a Spindle Gouge to turn the final shape followed by a quick tickle with

abrasives down to about 240 grit.

Decoration was applied with a Knurling Tool to produce a light pattern on the

wide part of the Barrel; either a soft brass or stiff bristle brush cleaned the

scurf out of the pattern;

colour pens or stains were applied with lathe set to a low speed in order to avoid

colour bleeding unintentionally into adjacent areas.

The Notch/Slot was cut with a Gentleman's Saw or

something similar with a rigid blade. The first clean crisp cut was

vertically down the whistle from the join mark between the Mouthpiece and Bore

Notch to a depth short of halfway. The next flat cut was angled to meet the down

cut. With the cut-out removed, Paul trimmed with a Chisel to improve the crisp

finish.

The Spindle Gouge finished the spherical end prior to sawing off and light

sanding.

Lastly :

♦ to adapt the spigot to form the Windway.

With it removed from the Friction Drive to expose the previously turned

dowel with its squared off face, Paul rolled up some 180 grit abrasives and took the

opportunity to sand the inside surfaces of the whistle as best he could in order to remove all

remaining 'hairy' bits.

The dowel was trimmed / flattened just prior to glueing in, lining up the flat

with the air hole as the glue went off and then the whole thing parted from the

friction drive. He chose to

sand underneath the Mouthpiece using a round cylinder of abrasives to a shape

resembling a Recorder's mouthpiece.

Once the Whistle was tested and as this was American Plane, he applied a little wax onto the outer

surfaces to seal up all pores in order to deter sweat & dirt stains. If the

whistle had been of Boxwood, Cherry or similar close grain wood, the outer

surfaces would not require waxing.

(photos by Andy Ogilvie, Rick

Patrick & Paul Reeves)

<to

index>

The subject for this meeting refers to a wide

interpretation.

It has been said that

Out of Sheds come Hobby Jobs.

Out of Workshops come Production Work.

but

Out of Studios come Gallery Pieces

Turned Wood Sculptures are not straight wood

turned shapes but rather something with a little more thought and intricacies

that are interesting to look at.

If you are lost for ideas, below are some quality examples of 'Gallery

Pieces' from our very own Members who have exhibited on previous Club Nights (My

apologies that I cannot confidently identify the individuals)

(click this one below for closer view)

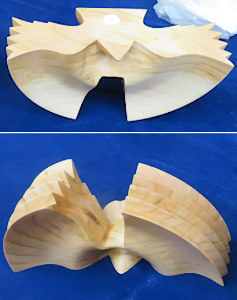

Multiple Centres Turning with Paul Reeves

The photo immediately above was for a competition to create something "From a 3 inch Cube" which Paul had band-sawed into six ½" thick squares. He commented that a better starting point would have been a similarly thick quarter-sawn plank (which starts off smoother than any bandsaw cuts) before creating the squares or whatever shapes you decide upon. For this demo, he had spent longer just sanding the 6 squares at home than the entire Club Night time this evening.

He first decided upon a concept for the

'sculpture' - he chose the theme of 'Night into Day'.

The procedures require the use of a large faceplate which must be very flat,

absolutely square to the turning axis and readily able to take off and replace

back square again. The faceplate needs to be prepared with sanding sealer on

front & back surfaces for double-sided sticky tape to function properly. As some

of the turning will be considerably offset, one might need to stick counter

weights on the back of the plate away from gouge tips.

From the photos below, it shows where the frames

were mounted when they were cut. Please note in the Offset photo, the 2

inner arcs were completed first before the Middle & Top frames were removed in

order to complete the outer arc on the Second Down frame. (Top frame had

inadvertently moved prior to photographing).

The Centred photo shows how the Suns & Moon were turned.

Only when both faceplate and frame backs were

wiped clean from dust with a Tack Rag, was a frame mounted into the correct

position with at least 2 strips of double-sided sticky tape; 3 strips perhaps

for the far offset frames. Paul used strips running the full length of the

frame's back for a more secure fit.

Paul only used the tailstock to help press the frames onto the faceplate before

it was withdrawn to leave room for working with the toolrest.

The V-shaped grooves were made with a short handle ¼" Spindle Gouge. As

all groove work was intermittent cutting, the gouge had to be moved gently and

carefully to avoid prising the frames off their mountings. It helps to

support the back of the tool to dampen the jarring effect every time the tip

comes into contact with the edge of the frame. Using abrasives afterwards

was not an option so the cuts had to be accurate and each groove of the same

size. Before starting, he had used soft lead pencil marks on the frames to

highlight where the grooved arcs were meant to be as anything paler would

disappear when spinning, particularly those further from the centre.

Paul advised against using a 3 point tool because when applied with intermittent

turning, they tend to barge into the edges of wood rather than a gouge slicing

the wood away.

The Moon & 2 Suns were individually mounted dead centre and their edges were cut

out with the gouge. They were finished off as an indented dome shape with

identical diameters (remember a total eclipse has the moon marginally larger

when viewed from Earth). When removed from the faceplate, they were further

decorated with 'rays' by using a powered Proxxon Veining Chisel. Paul considered

Sun rays should be conveyed with wavy beams while Moonbeams should be straight.

Once satisfied, he re-trimmed the outer edges of the heavenly bodies.

Next was scorching in the 'night' frames. Rather than using his heavy duty plumbers torch, Paul had found the Draper Gas Torch (running off gas lighter fuel) perfect for tidy controlled burning. This was followed by cleaning up and painting in the grooves - silver for the moonlit frames and gold for the sunny ones. Finally, the frames were attached together with Panel Pins as studs and with glue.

(photos by Andy Ogilvie, Rick

Patrick & Paul Reeves)

<to

index>

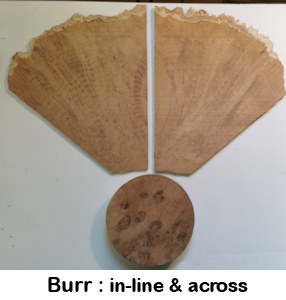

Jewellery is worn for several reasons. Whether

personal or functional, it should be comfortable while avoiding being heavy or

rough to wear! A small item or groups of small items are consequently

ideal, but in order to be distinctive when small, one needs to either select wood that

is more

striking than ordinary, or else a plain wood that can be made interesting by

decorating with texture, coloured waxes or resins filling indents etc.

Sometimes, off cuts from previous projects can be a good source but be wary of

loose grain wood which will lack sturdiness and liable to break up when thinned.

Below are some suggestions of what to keep an eye

out for.

(click for close up view)

And below are some examples of jewellery turned on a lathe :

(most of below can be clicked for close up view)

At home, Andy had used a set of Pen

Jaws which gave more distance / leeway for knuckles not to be rapped whilst

doing close work, whereas at the demo, he only had External Safety Jaws which

gave problems of limiting the techniques available and also left slight witness

marks from the jaws' tight hold of the previous work. The use of Pen Jaws (with

their round insides) minimised these marks as well as reduced the chance of

drawing blood!

A good alternative chucking solution might have been a Collet Chuck.

A

spindle square blank of Boxwood had been turned to an approximate 12mm dowel.

Having mounted the dowel as suggested in his tip above, Andy used a Skew to trim

the dowel side true before clean cutting across the protruding end. He

used the Skew edge to scrape off the corner of the end face to about 45º but

left the end face with a 3mm/4mm flat circle. Using the Skew again, he scraped the 2 new

corners he had just produced which left the dowel end approximately

hemispherical. He marked the piece about 9mm from the end to where the

earring would eventually be parted off. He sanded the piece with some 240 grit

abrasive while he still had a smooth shape to work because his next cuts (with a

small 3-pointed tool) created a circular cove around the end and a further 4

similar depth coves about every 30º around the shape, which would make it impossible to

obtain a smooth flat surface without spoiling the coves' edges. He used

the side of his 3-point tool for the last shape to the part off mark to suggest

a continuation of the sphere shape. He parted off ensuring the base was at least

8mm diameter to accommodate the Stud Post after sanding the base flat to receive

it. It just remained to repeat the process and superglue the Stud Findings onto

their bases.

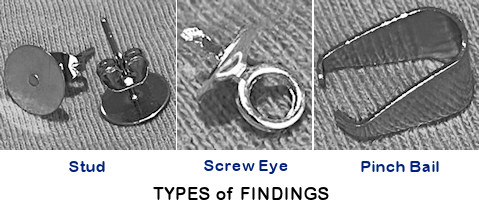

NB : 'Findings' is the general term used for jewellery fixings.

Necklace

To

highlight other ideas,

Andy had examples of Pendants & Bracelets (photos above) with contrasting wood

combinations and a pine cone enveloped with resin and turned thin.

To

highlight other ideas,

Andy had examples of Pendants & Bracelets (photos above) with contrasting wood

combinations and a pine cone enveloped with resin and turned thin.Andy also suggested that 'findings' including Screw Eyes and Pinch Bails could be obtained by typing something like "Jewellery Findings" into your browser to generate plenty of options from the likes of eBay, Temu, Amazon etc although anything silver does tend to be expensive.

Paul displayed a few examples of his own made

jewellery including 3 Lollypop Hair Pins made of Rosewood stem with Oak hand piece plus Irish Bog Oak as dark

pin head; some blanks for Silk Scarf Rings; Bangles (70mm minimum for getting

over a lady's hand); a burr toggled Pendant (which he knows better as 'Greta's

Badge of Office') and a Pink Ivory Ring.

He pointed out that any burrs within Jewellery must NOT have any sharp edges

left on the piece but can be removed by filling in

with wood dust and superglue to smooth them over.

Silk Scarf Ring

Bowl Squares were bandsawed or

gouge-turned

into cylinders of 50mm to 60mm diameter. The blocks had been prepared with 12mm holes with at least 10mm

clear between their adjacent edges. Paul had found that twist drills tended to rip the

edges upwards so he used his sawtooth drill bit to produce clean even holes.

When a silk scarf is of colourful or intricate design, one might prefer the ring to

be plainer so as to not compete with the beauty of the silk. Perhaps like

the pale wood above, which has its outer rim decorated with an Elf and gold gilt

cream to make it 'interesting'. When the scarf is just a single colour,

then a more striking wood might be appropriate.

Whichever is chosen, when the scarf is in position, it will cover up virtually

all of the centre of the ring.

This demonstration was with a block of Brown Oak. It had been pre-drilled with

two 12mm holes so the first job was to smooth and shape the front face with a

small ¼" Spindle Gouge. Because of having to cut with those holes coaxing a

gouge tip to drop in and cut the oncoming hole's edge, it is important to avoid

having a heavy push of the gouge onto the wood but instead have a firm hand

controlling the gouge on the toolrest with just a gentle pressure onto the wood

while moving towards the left. This control is helped with increased lathe

speed. Paul planned to smooth the centre and to take more wood out towards the

edge while leaving a raised rim edge. This was achieved by starting off

with the gouge cutting with its tip and left wing at the centre of the piece but finishing by rolling the

gouge so that only the central tip was cutting at the moment it reached the edge

of the rim. This required a lot of hand movement; the gouge tip might have moved

1cm while the handle had moved 4cm while tip and handle both had to keep moving in

the same direction. The right hand has to catch up the left by moving in a

longer arc.

One could also use a Skew/Scraper in the same fashion as Andy had done with his

pegs above.

With the lathe speed slowed and the toolrest moved out of the way, Paul set

about sanding a ring with 2 holes. With the lathe turning, one must not hold

abrasive with an edge facing upwards into a down coming hole. So if the

lathe is turning, hold

the abrasive in your fingers so that it hangs on the same side as the rotation

direction. If you didn't, the loose abrasive edge would snag in the holes.

Bear in mind if you reverse lathe

direction or you choose to sand from the other side of the rails, you will need to reconfigure the abrasive in your hand.

Ideally, doing your tool work well reduces the time needed for sanding with your

lathe turning. Paul finished off sanding with the lathe stopped and used 240

grit to gently round off the edges of the holes to ensure the silk wouldn't snag

on any roughness.

Finally, a thought had to be given as to how thick does one part off. Too

thin risks the ring snapping in half; too thick risks its own weight will

overcome the friction of the two silk corners going through the holes and fall

off. Paul used a thin Parting Tool, which seemed contrary to select when

it's designed purpose is to cut across single grain direction of spindle wood.

However, provided the tip is very sharp, this tool does a good job of getting a

smooth and flat back face with little further sanding.

With Brown Oak being quite tight grained and dense, Paul parted so that the ring

thickness was about 5mm. He made the cut wider than the width of the tool

so that the final parting cut was away from the back face in order to avoid any

grain pull-out in the piece.

Pendants

The bottom line with this example is that most people hold their blanks too

firmly which is unnecessary so long as you are careful with your tooling. For

example, if working on the back face without checking the pendant is steady in

its setting, a heavy hand on your gouge could press one side in, which might

flick the other side away from the sticky tape and spoil the whole cut. Once it

was cut gently & smoothly, Paul chose to decorate the back with a couple of

concentric circles, just because he could.

When it came to sanding, Paul had carefully tooled some detail on both sides and

aware that those crisp edges would be quickly removed by abrasives, he opted to

carefully tidy the surfaces with 320 grit and finish with a bit of wax and a

Pinch Bail Findings to connect to its cord.

The November 2024 Competition was set to turn attractive piece(s) that can be worn for personal adornment

(photos by Andy Ogilvie, Rick

Patrick & Paul Reeves)

<to

index>

August 2024 DEMO

3

Straight

from

Tool turned pieces with

Paul

Reeves

Paul

Reeves

Thu 15th August at MWCC Club Night

Straight from the Tool is a technique that

provides the best possible turned surface without requiring any use of

abrasives. To perfect this, takes time & skill.

Indeed, it wasn't until the 13th century before sandpaper was

invented in China and before then, any wood turning had to be left as tool

finished with the possible exception of refinement using wood shavings and (in a few parts of the

globe) fish skins.

Trying to complete a turned piece "straight from

the tool" shows up one's Tool Control, Tool Sharpness & Lathe's performance in

absolute clarity.

Control relies upon practice & experience of getting the bevel

position correct;

Sharpness comes with recognizing when a cutting edge needs attention;

Performance deteriorates from adverse vibrations caused by worn bearings of

headstock drive centres and/or tailstock centres or even a lumpy toolrest while

moving one's gouge along it.

Some turners have no alternative to turning this way - for example,

the fascination of Pole

Lathe turning is the hand-made look of natural tool finish;

Ornamental Lathe

turning relies upon intricate sharp-edged decorated pieces that would be ruined

by sanding.

How many of us take time to just practice using our gouges to achieve a smooth

finish, particularly with a 'difficult' wood to work, eg Paraná Pine? You

will quickly discover

that you need to select the right wood for the project,

that sharp tool edges are essential and

that high lathe speed is often your friend.

Spindle Work

Along Grain :

Paul had a piece of Paraná Pine mounted between centres and knocked the corners

off with a Roughing Gouge presented at right angles in the first instance to produce a

cylinder with a dull finished surface. This surface was improved by

presenting the same gouge angled at about 45º from vertical with the bevel

smoothing off the freshly cut surface as it moved along the tool rest. An even

better finish is with a Skew Chisel achieved by raising the toolrest so that

only the lower third of the tool is in contact with the upper quadrant of the

piece, which avoided adverse twisting of the tool in your hand and sliding

off the rest. The German Christmas Decoration turners of Seiffen use a square

ended tool but angled Skews are invariably used by us. These Skews have cutting

edges angled either straight or curved in an arc. The curved type have the

advantage of finer control by easily adjusting the cutting point by up/down

movements of the handle but the more acute the angled edge cuts the surface, the

more difficult it is to stop the cut moving in/out creating ripples so it does

demand very steady hand movements. The straight angled Skew is more stable for

the occasional Skew user.

Top Tip

: if using

any angled Skew, use the edge with the shorter side resting on the toolrest - or

in other words, with the acute angled corner uppermost. Move with your

body rocking on your legs rather than moving hands with your arms.

The Skew finish can look and feel like you've sanded down to 800 grit and

frankly, any use of abrasive is likely to be detrimental.

Cross Grain : Paul demonstrated different tools one could use.

①

His ¼" Beading & Parting Tool was shocking at cutting across grain causing

multiple pull-outs;

② His thin tipped Parting Tool

had less contact damage which was fine with close grain woods;

③ His Skew had the best finish

provided he only cut tiny slithers (about ¼mm)

successively but this time with the longer side resting on the toolrest (i.e. sharper

angled corner lowermost).

Beads and Coves are also cutting across the grain of spindle work and require a recently sharpened Spindle Gouge to cut from larger diameter to smaller. These procedures were previously described back in May 2024 and can be found in 'Spindle Revision' < here >

Bowl Work

As the walls of a bowl comprise of a

combination of along/side grain and across/end grain wood, fresh cut blanks will distort

as they dry out.

It is essential for the dried blank to be held solidly in your chuck jaws when

you are ready to finish it, so some thought should be put into how to rough your

bowl in preparation.

Bowl blanks are best roughed out to a wall thickness about 10% of the overall diameter as this is

average shrinkage amount around the annual rings and leaves plenty of room to

true up later. Some woods eg Alder, Yew hardly move at all whereas Cherry (as

you can see from the picture below) moves a lot during shrinkage when the wood

also warps in two directions; i.e. the opposite sides

that are along grain will shrink closer together and to a lower height than the

across grain sides.

Paul anticipates this by roughing the blank so that the spigot on the bottom is

finished with a pop mark in its centre and pencils the date on the bowl's lip.

If the roughed out bowl is either wide or shallow enough for a chuck key to

operate, he additionally creates a dovetail spigot inside the bowl bottom

together with a pop mark there too. Note

that some chuck keys have hexagonal ball ends that can still adjust the jaws at

oblique angles.

Once dried out many months later, the outside

spigot will be oval and will need to be re-trimmed circular, ideally to the

'True Circle' jaw diameter in order to be held rigid even if the spigot is only

a few millimetres proud.

This can be achieved by :-

either driving the piece between a Jam Chuck acting against the inside of

the bowl and a tailstock centre pressing into the pop mark,

or if applicable, with a chuck gripping the prepared inside dovetail and with a tailstock on

the pop mark.

Outer Surface

Paul's Walnut rough blank did have an internal dovetail - but first, he gripped

the outside oval spigot as best he could with the inside supported by the tail

stock in order to level off the lip of the bowl.

Then with the piece remounted with long-reach or o'Donnell jaws to the inside

dovetail together with a tailstock to the base pop mark, he re-trimmed the base

spigot to true circle as described above.

While mounted in this position, he applied pull cuts from the centre to about

halfway up the side; if he had continued any further, he would be dragging the

tip over wood that was rapidly changing from side grain to end grain twice every

revolution, which would end up rough - particularly with hard dried out wood.

In order to give a better surface cut, one can change the pull into a push cut

by moving the tool handle from in front of to behind the tip in one deft

manoeuvre such that the bevel will now smooth the cut onwards to the lip of the

bowl.

Unfortunately, this Walnut bowl was so hard in places that it was difficult for

Paul's gouge not to be kicked about uncontrollably. There were 3 likely

explanations :-

1. Combination of the lathe speed & the gouge were moving too quickly;

2. Pushing too hard down on the gouge;

3. Cutting tip was above centre and the hard parts of the grain were

ending up bouncing against the bevel resulting in only the softer wood getting

cut away leaving the hard pieces getting relatively higher, aggravating the

fault.

Incidentally, if one resorted to abrasives at this stage, it would compound the

situation because more would be lost off the softer along/side grain than the

denser across/end grain resulting in a change of bowl shape. In Paul's

Walnut bowl piece, this was further accentuated as the sides were sapwood and

the ends were heartwood.

The solution is to carefully cut away the hard parts in tiny amounts on each

pass. All other methods (e.g. scrapers) are likely to result in pull outs.

Sharpening

your gouge or changing to a smaller tipped gouge can help.

To remove tool marks, a useful ploy is to use the lower wing of a Bowl Gouge to

gently dress the surface with a slight shearing angle. Be careful to

ensure the top wing does not touch the piece with this method. Many

of us sharpen gouges with a 'fingernail' profile whereas a straight edge wing

profile is better for this job.

Sanding Sealer (quite acceptable for tool finish pieces) will help to stand up

the wood fibres making it easier to cut them off.

Top Tip

: Although the wood fibres are now standing proud, they are all

still bent over in one direction. If your lathe is capable, when getting to your

finishing cut, try reversing the direction of turn and with the tool rest and

gouge/shear scraper positioned to the far side, you will now be cutting from

underneath the raised fibres, resulting in a much smoother finish. This is the

same reason that changing direction of turn with abrasives is so effective.

This will work for both inside & outside surfaces. NB Beware that heavy

contact could start to unscrew the chuck from the head stock.

After applying Sanding Sealer with brush or

cloth, pressing paper with lathe turning created heat to help dry the sealer

off. Now when you pass your gouge over the piece, wherever the surface is low,

the untouched Sealer shows up as still shiny.

One also needs to consider whether the surface you are working will be in

contact with food, in which case use water instead of Sanding Sealer to stand

the fibres up.

Inner Surface

With the piece remounted on the base spigot, Paul

quickly removed the inside spigot in order to be able to make one continuous

pass for the following cuts. Whenever one stops a cut and restarts again,

it is inevitable that a witness line will be left on the surface.

One remedy is to use a curved surface tool. Although it is better to cut

rather than scrape, smooth movements, for example, with a Negative Rake Scraper

can provide the finest surface finish. However, the drawback is the edge doesn't

last very long and needs regular tickling with the diamond file whenever the

shavings become irregular. Reapplying Sanding Sealer often helps when you are

near the final passes.

The correct use of a scraper is to position the toolrest so that the tool is

slightly handle high with the cutting edge at the 9 o'clock position. If your

Scraper (e.g. Taylor Teardrop Cutter) has a round bar sitting on the tool rest,

one can avoid the tendency of the end grain parts of the piece from being

levered up by twisting the tool anticlockwise such that the scraper edge is at

an angle, which will help to slice the surface.

Now it is just patience and care to

remove all the tool marks as best that you can by trying to reach the same

colour without the Sanding Sealer highlighting any lows.

Paul finished with shaping the rim and its inside edge with his Negative Rake

Scraper while carefully supporting the outside surface with his fingertips.

The September 2024 Competition was set to turn piece(s) without any sanding - although oil/sealer finishes are acceptable

(photos by Rick

Patrick & Andy Ogilvie)

<to

index>

June 2024

DEMO 2

Mixed Solid Media with

Andy

Ogilvie

Andy

Ogilvie

Thu 20th June at MWCC Club Night

SOLID MEDIA refers to different materials that

can be worked.

These include :

wood

soft metal

epoxy resin

acrylic

Perspex

Corian

Milliput epoxy putty

etc

A piece of wood with just paint, pyrography or made out of 2 or more different types of wood doesn't

strictly satisfy the

criteria of

MIXED SOLID MEDIA,

whereas, two or more combinations of the above examples does, whether used within the

body of the piece, or as a decoration.

For example, Andy had used

Perspex as a lid to his wooden kitchen Salt Pot to

keep moisture out while able to see what was in that particular pot;

turned

Corian to enhance an opening;

napkin rings decorated with Milliput;

a Laburnum

urn decorated with brass rivets.

(click for close up view)

(click for close up view)

In précis, Mixed Solid Media pieces

can be :-

♦ COMBINATIONS of the above media or kits (egg timers, clocks, pens etc);

♦ DECORATIONS of solid media applied to a piece;

♦ INTEGRATED MATERIALS which form a blank for subsequent turning.

This demonstration will give more

detail of how to achieve some of the above processes.

Andy warned that using open-grained wood had difficulty in maintaining a sharp

edge between wood and putty/metal alloy once the piece had been sanded back to a

smooth finish, because the slurry had a tendency to penetrate into the wood

grain resulting in a cloudy grey effect near the joint between the media.

For his demonstration, he had chosen Boxwood.

Andy's basic message was, "Don't be put off with experimenting with these

various materials just because they are unfamiliar. They are all manageable."

Milliput Epoxy Putty

Milliput comes in 2-pack blocks of putty in black, yellow grey, silver grey,

terracotta and superfine white, (the latter can be used for creating very fine

details). In preparation for applying his Milliput around the body of his

box, Andy used a Parting Tool to create a recess about 3-4mm deep and about 5mm

wide, although he deliberately countersunk the sides to be wider at the bottom

of the recess in order to help secure the putty in position once cured. After

cleaning the surfaces, he applied a coat of sanding sealer which would help

keeping the wood clean with a simple wipe.

When new, the putty is malleable

although it will be less so with age after opening.

Top Tip

: If putty has become stiff

with age, try working each block separately while under the stream of warm air

from a hairdryer but be aware that heating reduces the curing time and hence

less time to manoeuvre into situ. Adding a

little water can also soften the paste.

Having selected equal quantities of both parts, Andy mixed them well together before rolling out into a thin sausage and pressed into the recess while aiming to minimise gaps/holes. There was no need to skimp on the amount used because it cleans off easily and used for the next recess. Andy often uses different width of recesses to create interest.

Depending upon temperature and age of putty, it would take about 2 - 3 hours for the Milliput to 'cook' and harden off enough before one could turn the piece with a gouge or sand back. Milliput can be readily shaped by gouge and particularly receptive to sanding.

Andy also described other effects that could be produced using different coloured putty like the black and white chequered feature shown below.

Soft Metal

Andy had brought along some "Wood's Metal" bars of bismuth/lead/tin/cadmium alloy which have a

surprising low melting temperature of 70ºC (not much hotter than solder) and

would melt in a spoon with a hot air gun, particularly when the

alloy bar is cut into tiny pieces. He warned against using solder as it

tended to be difficult to pour without solidifying before it filled up all the

space and it doesn't polish up as well as the alloy. Pewter is a suitable

alternative but requires higher temperature to become molten.

As we are relying upon gravity to help us, trying to cast a metal ring around

the side of the box is a difficult process. However, flat surfaces like a box

lid are perfect.

So while the lid section of his box was still connected to its body on the

lathe, he prepared as he had done for the putty by forming a countersunk recess into the end of the piece but then added a slight bevel to

the edges of the recess; these bevels encourage the molten alloy to fall into

the recess.

After cleaning the surfaces, he again treated with a coat of sanding sealer.

With the lid now set flat, the chips of alloy were placed in a spoon and heated with a hot air gun until molten about 45 seconds later when it was poured into the recess. Enough alloy was dropped in for the meniscus to just bulge above the prepared bevel. This was to allow for any dipping as the alloy cooled & solidified. Dependent upon the volume of alloy used, it should be ready to work within 10 to 30 minutes. The aim was to minimise wastage and to have very little to turn away with a gouge. Before any sanding, another coat of sanding sealer was applied and subsequent abrasives were carefully used lightly with fine grits only & at a slow speed to avoid frictional heat re-melting the alloy.

Integrated Resin

A quick Google search for "resin for beginners kit" will show there are many

suppliers out there, which might seem daunting but can be rewarding with a

little perseverance. There are 3 types of resin; Epoxy, Polyester &

Polyurethane but epoxy is best for gaining experience. Many starting sets

are for thin projects but woodturning

projects tend to require several centimetres thickness, which you will need to

consider before buying.

They all require mixing of the resin with a hardener. The deeper the

cure mixture, the more that stirring and higher curing temperature can create

bubbles which would detract from the finished article. To overcome this problem,

some suppliers sell specific epoxies & hardeners for different depths while some

guide you to different ratios of resin to hardener. Others explain how to remove

bubbles using heat guns or even toothpicks! One method includes using

pressure pots that will compress air bubbles to sizes so small that you will not

be able to see them, in order to achieve a high quality clear casting at the

cost of several hundreds of pounds Sterling!

Not surprisingly, the duration of the curing process is variable from maybe 10 -

24 hours so it is always best to leave the turning for at least a day.

"How to make a combination of wood and resin blank for

turning" is best done by asking Google that very phrase and watching one

of their helpful videos.

The basis is :

Prepping the mould with the wood;

Put in some means for the chuck jaws or screw chuck to grip;

Tape the wood down so that it doesn't float away when the resin is poured in;

Mix the resin and hardener;

Stir in colour/sparkle as desired before pouring;

and leave for at least 24 hours.

Next day, you should have something like Andy's photo above; the Polyfilla tub acted as the mould and he has already used the lathe to create a new spigot for the base of the bowl whilst mounted in the jaws using the wooden spigot partially buried in the resin. Andy had found that warming up the hardener/catalyst seemed to help it mix with the resin more efficiently and he advocated leaving the mix still for 15 mins to give bubbles a chance to dissipate. He had added a blue tint and some sparkles.

Much of the initial sanding of the resin piece was with a 50mm padded drill attachment but after fine abrasives and spray lacquer to finish, it looked like this ...

The July 2024 Competition was set to turn any piece of combination, decorative or integrated styles that incorporates two or more Mixed Solid Media

A

Cautionary Tale - Having seen some bamboo

stalks encased in resin on You-Tube, Andy told of his attempt to incorporate

this idea into one of his projects. To the left, you can see the pot

within which he had arranged a circle of bamboo to be set in some resin, somewhat

mimicking an orange. After allowing to cure and fitted into a chuck, Andy

experienced a catastrophic failure when upon starting the lathe, the resin

failed to hold the whole piece together and the orange suddenly broke up into 'segments'. You might spot in the photograph that some significantly large

pieces detached themselves and indeed there is one piece still in the workshop

somewhere he cannot find. The reason is uncertain but possibly a combination of

excess moisture within the bamboo and the thinness of resin bridging the edge to

the centre. As Andy is accustomed to do whenever he starts turning a new piece,

particularly with an irregular

shape on the lathe, he was wearing his face shield, which did exactly the job as

its name implies.

A

Cautionary Tale - Having seen some bamboo

stalks encased in resin on You-Tube, Andy told of his attempt to incorporate

this idea into one of his projects. To the left, you can see the pot

within which he had arranged a circle of bamboo to be set in some resin, somewhat

mimicking an orange. After allowing to cure and fitted into a chuck, Andy

experienced a catastrophic failure when upon starting the lathe, the resin

failed to hold the whole piece together and the orange suddenly broke up into 'segments'. You might spot in the photograph that some significantly large

pieces detached themselves and indeed there is one piece still in the workshop

somewhere he cannot find. The reason is uncertain but possibly a combination of

excess moisture within the bamboo and the thinness of resin bridging the edge to

the centre. As Andy is accustomed to do whenever he starts turning a new piece,

particularly with an irregular

shape on the lathe, he was wearing his face shield, which did exactly the job as

its name implies.

(photos by Rick

Patrick & Andy Ogilvie)

<to

index>

Thu 16th May at MWCC Club Night

Thu 16th May at MWCC Club Night

To clarify, you use Spindle tools when all the

wood grain of your piece is running parallel to the lathe bed.

Spindle

tools include :

Roughing Gouges (rarely used

full name is SPINDLE Rouging Gouge);

Spindle Gouges;

Parting Tools;

Skew Chisels;

Form Tools;

Roughing Gouges are designed to be used

only for spindle turning and NOT on bowl turning. They are tough

enough to take the knocks required to turn a square into a cylinder so long as

you're careful with how much you bite in one go. Taking a large bite will blunt

the tool edge quickly; taking too much could bend or break off the gouge. This

is because they are of relatively thin, forged steel and often tang-mounted into

their handles and despite their name, cannot survive such rough usage!

They come in various sizes but all are best used with the bevel ground to 40º -

45º; a common mistake is to sharpen the bevel at steeper angles which will end

up chopping the corners off badly and tearing the wood.

Use with the handle down and move the tool along with arms and body together

while rocking sideways on your feet. The toolrest hand can deflect shavings away

from the face. Too much down pressure results in an uneven jerking cut;

moving too quickly normally produces a spiral finish.

Next to consider is with the gouge perpendicular to the piece, the surface

getting cut is arriving straight onto the gouge and getting levered upwards

which leads to a less than smooth tool finish. This is helpful for quick removal

but for the final pass, holding the gouge so that it is angled about 45º from

the perpendicular, the cutting edge is presented like a skew which will now

leave a shiny smooth finish. With a careful steady hand, you will produce a

straight surface. The only other shapes to make on a spindle are 'beads' and

'coves' with .....

Spindle Gouges. A bead is started by just

rotating and rolling the gouge anticlockwise along the toolrest for the left

side and similarly clockwise to form the right side of the bead. These movements

will only cut an arc equal to its bevel angle. To cut beyond that arc, the

handle has to be moved and lifted (because the diameter has become smaller) in the same direction and in coordination with

the rotation so that the gouge tip and bevel end up perpendicular at the desired

edge of the bead. This means the handle end has overtaken the tip.

For a cove, start with the gouge on its side, flute towards the intended cove

and use your fingers on the toolrest to balance & guide as you rotate the gouge

to end flute up at the bottom of the cove. As with the bead, the movement

requires coordination of slide across toolrest with rotation, handle descending

and when approaching the bottom, a conscious gentle push into the wood for the

bevel to stop the tip from digging in and producing a pronounced line where the

opposite cove side ended. Tools with long handles normally provide better tip

control - for every inch the handle moves the tip around the toolrest hand, the

short tool affects the tip movement far more than a long one. However, with

beads and coves requiring so much hand steering, a short tool makes it easier to

manipulate without your body getting in the way. Unfortunately, if the tool's

flute is short because of the metal has been ground back so many times, it may

be short but you are probably cutting with high speed steel rather than the

hardened which keeps its sharpness for longer use.

This gouge can also produce a straight surface by using your fingers as a

resistance or brake while your handle hand steers the tip so that it remains at

the same angle and distance over the toolrest with the cut running level. When

cutting towards the left, It is important for the flute to be angled towards

your left shoulder such that the cutting edge is just left & lower of tip centre;

likewise when cutting towards the right, use right shoulder and just right & lower

of tip centre.

Parting Tools are regularly used to

accurately block out a smaller cylinder guided by callipers. They come in

various shapes in an attempt to avoid friction when cutting wood which leads to

swelling up and binding/grabbing on the sides of the tool.

Parting Tools are regularly used to

accurately block out a smaller cylinder guided by callipers. They come in

various shapes in an attempt to avoid friction when cutting wood which leads to

swelling up and binding/grabbing on the sides of the tool.

Skew Chisels come to the rescue of a clean

finishing cut across the end grain of spindles. Parting tools tend to tear out

the end grain unless the wood is particularly close. With a Skew, you must only take off thin

bites at a time so that the removed wood is a thin disk being skimmed away.

Skews can also cut along the grain with a bit of care. Production turners

of yore and the Seiffen wooden Christmas Decoration turners of Germany today

used Skew Chisels for most (if not all) their

shaping. Skews come in many bar shapes and widths. As most of us have missed out

on the 3 year apprenticeship of Seiffen folk, the occasional user should select

a small width bar which has the advantage of producing a lower rotational force

in your hand than a wider bar would.

At all times, you are trying to avoid the

wood grabbing the cutting edge and twisting the tool out of your hands. This is

best achieved by raising the toolrest so that only the lower third of the tool

is in contact with the upper quadrant of the piece. In the photograph to the

right, you will see that when the trailing corner edge is being well

supported by the toolrest, the Skew is cutting away the wood with minimal

twisting force and neither corner is in danger of getting snagged. Keeping

wood contact within the green area makes the cut stable. Touching in the red area

is liable to twist the bottom edge of the tool off the rest and out of control.

At all times, you are trying to avoid the

wood grabbing the cutting edge and twisting the tool out of your hands. This is

best achieved by raising the toolrest so that only the lower third of the tool

is in contact with the upper quadrant of the piece. In the photograph to the

right, you will see that when the trailing corner edge is being well

supported by the toolrest, the Skew is cutting away the wood with minimal

twisting force and neither corner is in danger of getting snagged. Keeping

wood contact within the green area makes the cut stable. Touching in the red area

is liable to twist the bottom edge of the tool off the rest and out of control.

Another useful cut with a Skew is a V-cut to transition the square top section

of a table leg (aka pommel) into the largest circle that the square timber can

form by enlarging the V shape until the groove is so deep that it nearly meets

at the centre of a flat side.

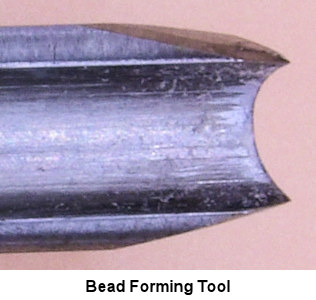

Form Tools - usually bead forming tools

are fine until they are used on soft woods. When they are wriggled from

side to side and the tool has cut down to near the crown of the bead, there is a

likelihood of the grain to chip out on opposing sides where it was very short and

parallel. The Spindle Gouge will make a better job with soft wood. The photos

below show how the Bead Tool is presented to the piece, i.e. groove downwards;

to help the wriggle action described above, note the outer wedge shape grind in

the 2nd photo and the last shows some home-made Form Tools, although the lower

is making use of the last bit of the flute so it is likely to be primarily mild

steel rather than the treated hardened steel that was there when first bought.

Another tool

(popular in USA) that can be used on spindles are Solid Tipped Carbide Lathe

Tools although they seem to tear most of our native timbers, but good with close

grain wood types.

Paul then produced a Policeman's Truncheon as an ideal project to perfect all the spindle shapes discussed above.

(photos by Rick

Patrick & Paul Reeves)

<to

index>

May 2024

DEMO 1

Gavel with

Paul Reeves

Thu 16th May at MWCC Club

Night

As there were several newcomers to the Club, Paul started off with some

Revision of Spindle Work.

An account of this subject can be found <HERE>

Honorary Member, Greta Reeves worked many years at Lymington Auctions and it

became practice that her boss would arrange for a replica of his own

Auctioneer's Hammer be turned as a retirement gift for long standing employees.

His original was of Cocobolo but the replicas were turned from more readily

available Laburnum. This original was tactile & small enough to grip the head

comfortably in his hand. Consequently, the handle didn't have to cope with

much blunt force and didn't need a strong thick connection to the head. The 3

examples below are Box, Laburnum and Mohonia.

The

head and the handle are both spindle components turned separately and

subsequently glued together.

The

head and the handle are both spindle components turned separately and

subsequently glued together.

Despite recent demonstrations venerating the 'Golden Ratio' of 1.618, the

dimensions of these gavels are such that the handle is twice the length of the

head. The length of the head was twice its own diameter. Additionally,

dividing the head into four gives a far better proportion for the two hammer

faces taking a quarter of the length each, leaving the neck between them for the

remaining half.

Head

A prepared cylinder of Laburnum was mounted between centres. Paul advised

against using sprung steb centres at either end as he found the sprung central

point applied to end grain tended to split the piece when under tension.

He had planned this project to have a 1½" face diameter, 3" head length and a 6"

handle.

He used a narrow Parting Tool to mark out the ends of the head and pencilled in

the quarters between them.

Using a wide Parting Tool making half-width overlaps, Paul quickly removed waste

from the neck.

Having prepared callipers to ¾" for the diameter of the neck, he used the

Parting Tool to finish blocking out accurately.

As both hammer faces were to be near spherical, he pencilled in marks around the

piece about ¾" from each end which is where the face would be at its maximum

diameter.

He then started making bead-like cuts off the ends gradually working back

towards the pencil line but leaving it visible. It was important to avoid

getting the end pointy; it should look more like a puffed-up cushion. The final

cuts were made while maintaining a slow, smooth and light-touch pass with good

bevel contact throughout. If your hands end up moving quicker than needed, the

bevel will lose contact/support and the tip will catch the wood and dig in.

The trick now was to turn the other end to match! If you have changed

hands when holding tools to work in the opposite direction from your early days

of turning, you will find that very helpful in this case.

The

next details were to put in a small cove centrally where the handle will go and

to finish off the hammer heads from the pencilled line back towards the neck.

Paul favours a small decorative feature in these beads called a quirk, which was

achieved with a 2mm ridge left about 20º down from the pencil lines so that a

Skew could create a shallow crisp-edged V-cut and the bead continues down to the

neck. This was only a tiny detail but it certainly helped to focus attention on

the heads.

The

next details were to put in a small cove centrally where the handle will go and

to finish off the hammer heads from the pencilled line back towards the neck.

Paul favours a small decorative feature in these beads called a quirk, which was

achieved with a 2mm ridge left about 20º down from the pencil lines so that a

Skew could create a shallow crisp-edged V-cut and the bead continues down to the

neck. This was only a tiny detail but it certainly helped to focus attention on

the heads.

One might think it more sensible to drill the hole for the handle earlier -

perhaps even while the Laburnum blank was a square. However, now that the

current dumbbell shaping is nearly finished, the patterns of the grain lend

themselves for you to decide where to drill the hole in order to show them off

to their best when the gavel is at rest on a desk. Once marked with an awl or

similar, one could finish the sanding and drill the hole once removed from the

lathe. For the demonstration, Paul drilled the hole on the lathe by eye using

smaller drill bits as pilots and gradually building up to the final size.

Using a Skew, he decreased the supporting end nibs to about 4mm diameter which would be strong enough to hold the piece while sanding. With the lathe speed reduced to alleviate the piece overheating while sanding, Paul prefers to follow the curves by supporting abrasives underneath the piece and taking care to avoid sanding away detail and decoration by sanding the shape and not sanding to shape. Laburnum will abrade down to 1200 grit or finer with considerable success but Paul was going to finish this piece with buffing so down to 400 grit was going to be sufficient.

Handle

Another prepared cylinder of Laburnum was mounted between centres. Once again,

Paul avoided using steb centres following a previous attempt turning a Mahonia

cylinder down to an 8mm tenon for inserting into the head, because it split as

soon as he tightened the tail stock.

He aimed to carry out all the shaping and decoration prior to weakening one end

as a result of the small tenon being turned. Paul also advised that if the

intended gavel was to be used while holding a longer handle rather than a grip

around the head, you might want to consider reinforcing the tenon with a steel

brad/nail.

He also planned to turn the piece with the tenon at the tail stock end so that

when checking fit into the head, it could be easily remounted in the lathe for

further turning.

The decoration was a homemade creation from an old square-ended scraper with 3

grooves made with the corner edge of a grinder wheel. This results in 3 evenly

spaced and shaped tiny beads. Because he had carefully spaced the grooves

relative to the width, he could easily increase those matched beads to 4 (or 40

of them if you wanted) by using a previously cut bead to fill an outer groove of

the tool and guide further matching cuts.

An elegant handle is all about shape and curves. Paul used a thin Parting

Tool to mark out the ends, the tenon and the diameter of a spherical shape at

the bottom end. He quickly turned away the bulk to leave a rough shape before

changing to a short Spindle Gouge to refine to the shape below. Be aware

that keeping the tips of narrow spindles cutting at the optimum height on an up

and down surface isn't easy and needs a gentle contact pressure throughout to

avoid digging in. With close grain woods like Laburnum, there will be minimal

compression of the spigot so that requires starting from slightly oversized and

gently approaching the necessary diameter with regular retracting of the

tailstock to check the fit into the head.

When satisfied with the cut shape, start sanding up to the edge of any

decoration but be careful not to wipe away small beads and sharp corners,

particularly with your initial grits; they can be polished up with the edge of

the finer grits when you progress to them. Whenever sanding spindles with

the lathe turning, keep the abrasive moving and keep in mind that it is sanding

across the grain fibres so they will inevitably stick up. A technique to

overcome this tendency is to stop the lathe and finish that grit along the grain

before changing to the next. Don't sand the spigot because if it fits, you won't

want it made smaller and besides, a very smooth finish doesn't help the glue to

adhere to the wood.

A Skew reduced the ends with a series of enlarged V-cuts to a very small

diameter (still stable because the wood is so dense) and finally parted off with

a fine toothed saw aimed away from the piece so that the tiny pimple left was

abraded away with the last grit used.

The head and the handle were buffed

with a light touch using a buffing compound so remember to put on personal

protection in order to avoid getting grit flying into your eyes. Remember to

buff off a surface, not into

it, or else the piece is liable to be ripped out of your hands. The final finish

was some micro-crystalline wax.

When sticking the handle and head together, thought was taken to line up their

grains sympathetically.

The June 2024 Competition was set to produce a Gavel

(photos by Rick Patrick & Paul

Reeves)

<to

index>

I found it difficult to picture in my mind how to get 3 symmetric points out of

a solid with 8 vertices, 12 edges and 4 sided faces but then I remembered

something cubed is renown as a power of 3 and it does have 6 faces.

When Andy showed a finished 3-Point bowl alongside a perfect cube of wood,

one could clearly follow that the cube had somehow to be mounted symmetrically

between diagonally opposite vertices.

It was important that your starting cube of wood had 3 clean adjacent edges

because a small part of those edges furthest away from their common vertex would

comprise part of the finished piece.

It is possible to turn a thin walled bowl dependent upon the chosen wood.

Andy's example was of Brown Oak, which was close grained whereas an open grained

wood like Ash would prove difficult.

Andy had prepared a cube of Hornbeam with each edge of 100mm. This would

produce a finished piece whose points would be within a maximum 163mm diameter

circle. (Ratio of edge to span = 1 : 1.63 from Trigonometry)

Having decided upon the 3 clean adjacent edges, he proceeded to saw off the tip

of their common vertex in order for his tailstock to maintain a firm hold.

The opposite vertex was jammed into the headstock spindle with the aid of

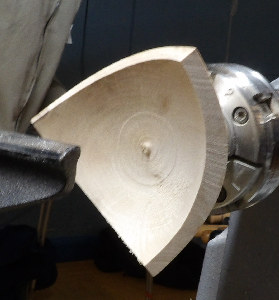

non-slip matting. He took care to ensure the headstock end was in its correct

position by checking, using his toolrest, that his chosen 3 vertices were passing it at

the same position.

Top Tip

: Once the lathe is turning, these angled edges will fade from

view so be careful to keep fingers on your side of the tool rest.

Also, with it turning, you won't be able to see exactly when the gouge will

start to cut so ensure that first contact is always with the gouge's bevel as

you slowly move towards the piece with the handle held low. Upon contact, the

bevel will make a 'bumping' noise which will suddenly dissipate when you

gradually raise the handle and the gouge tip starts to cut.

Andy started turning away the 3 vertices nearest the headstock by taking thin cuts with each pass in order to avoid rip outs

as each edge reached the cutting tip. A high lathe speed always help with

irregular surfaces but it is important to avoid any 'greedy' deep cuts.

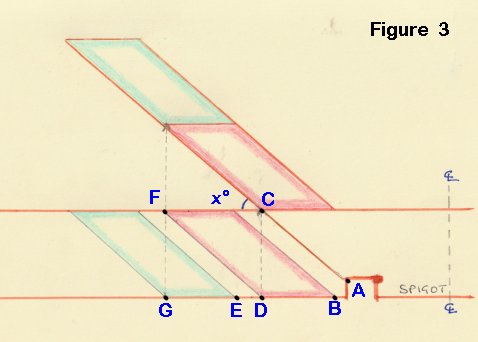

The spigot was to fit his 40mm set of C-jaws with a 7mm depth. Andy used his

thin parting tool to create the groove for the jaw lip at the bottom of the

spigot and then a similar groove half way up; this was for a later process.

Andy initially sanded with the lathe turning while using a power sander rather

than hand held abrasives in order to avoid the remaining sharp corners causing

injuries. He then stopped the lathe and hand sanded along the grain before

finishing with a coat of sander sealer.

The piece was then fitted into his C-jaws ready to hollow out the bowl. Andy

sawed off the newly exposed tip to accommodate support from his tailstock.

Taking care to avoid flying corners, he gradually turned away towards the centre

but leaving a stub for his tailstock.

As he cut closer to the flying corners, he regularly stopped the lathe to check

that his inside cut was keeping parallel over the entire length of the outer

edge of the piece. Any disparity quickly showed just how far down the cut

his Bowl Gouge needed to remove more wood to return the edges to parallel.

Halfway through the hollowing, Andy turned his toolrest into the hollow to avoid

a long over-hang of the gouge near the bowl's bottom.

Once satisfied with the inside parallel shaping, he removed the tailstock as

well as the stub to about 5mm from the bottom. Using a smaller Bowl Gouge,

he continued cutting to clean up the bowl's centre with just the chuck jaws

supporting.

When it came to sanding, Andy took care to avoid the abrasives

damaging any of the sharp edges. He didn't do any hand sanding with the

lathe turning, instead used his selection of various hard-backed shaped pads

without applying too much pressure. He found that his power sander with a

soft padding was ideal for sanding the central bottom of the bowl when applied

to the opposite side of where he was standing. With the lathe stopped, he