Pencil

Shooter

with

Paul Reeves

Thu 16th January 2025 at MWCC Club Night

The forceful characteristic needed to

propel a pencil is stretchiness, which can be obtained from elastic bands or springs.

The majority of online examples rely upon sawn shapes to provide strength for

supporting the stress & forces involved with taut rubber bands but as

Woodturners, we want predominantly turned components.

For this demonstration, Paul had chosen to use the energy provided from

releasing a compressed spring to fire a hexagonal pencil (doesn't

have to be a Reeves

pencil of course!) that is no larger than 8mm diameter.

The 'weapon' shown below comprises of a Barrel with 2 bore sizes to accommodate

the 8mm pencil through the Muzzle end and 18mm bore through the Breech end. The

firing mechanism is a combination of Piston (with a notch for a trigger), the

Spring and a Rod through the Breech Cap to the Knob, which holds everything together.

Barrel

Taking account of the length of his

Spring and about another 100mm of Bore to keep the pencil's flight true, Paul

had selected a minimum 200mm length of 35mm square blank of Beech for his

Barrel.

Mounted between centres, a Spindle Roughing Gouge turned it to a cylinder

suitable to be mounted in his 38mm o'Donnell Jaws. With the piece firmly gripped

in the jaws and a tailstock in support, a Skew Chisel squared off the end in

readiness for the Breech component to be a screw tight fit.

The tailstock was refitted with a Jacob's Chuck and an 18mm saw-toothed Forstner

bit, chosen because it was just bigger than the diameter of the Spring. The lathe speed was reduced and

while starting off carefully with the bit exactly centred, a hole was drilled deep enough to

accommodate the sum of the Piston & Spring lengths plus about 8mm for the

Breech's thread to screw into the Barrel. Once the first hole is done,

further turning & drilling will be easier to keep true.

Remember that handling a Jacob's Chuck does need care as highlighted in

our Top Tip <here>.

To reduce friction inside, the Bore was sanded smooth with abrasives wound

around a pencil.

Paul decided to enlarge the first

10mm or so of the Barrel so that the Spring/Piston mechanism would clear all

threads whenever inserted or removed; this only needed the

Bore to be increased about 2 or 3mm with a Box Cutter.

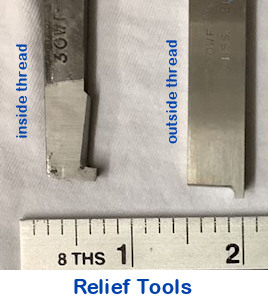

Next, a Relief Tool was used to

create a slot into the wall of the Barrel next to the step of the 18mm Bore

width. The thread is created with the Thread Chaser when it 'lands' and is

'taken off' in a smooth circular motion. That slot will allow freedom for the

Chaser to lift clear of the inside threads before it gets stopped suddenly

against the step down of width and would damage the threads already made.

Next, a Relief Tool was used to

create a slot into the wall of the Barrel next to the step of the 18mm Bore

width. The thread is created with the Thread Chaser when it 'lands' and is

'taken off' in a smooth circular motion. That slot will allow freedom for the

Chaser to lift clear of the inside threads before it gets stopped suddenly

against the step down of width and would damage the threads already made.

Beech doesn't often take a thread as well as some closer grain woods but in this

demonstration, a perfectly good thread was obtained with just half a dozen

passes without having to resort to wily ploys like stabilizing the wood grain

with thin superglue. The thread and bore were checked and any roughness

was dealt with by brush or abrasives.

The piece was reversed in the chuck

to expose the Muzzle end and aided by the tailstock, lined up for the Jacob's

Chuck (now fitted with a sharp 8.5mm drill bit) to drill its hole down the

centre. As previously, start drilling slowly before speeding up, watch for

clogging up and clear out frequently until certain that you have drilled through

to the 18mm bored hole.

Paul then used a countersink in the Jacobs to create a chamfer in the Muzzle

Bore. This will help later when the Breech Cap is completed and screwed on such

that the Barrel can be held between centres. Again, to reduce friction, this end

of the Bore was 'polished' using a drill bit in a powered drill.

Breech Cap

Taking another piece of Beech

already prepared to a cylinder and clamped true in the o'Donnell jaws, Paul used

a Parting Tool to form a parallel spigot with a diameter slightly bigger than

the enlarged Breech Bore. This spigot will take the male thread that will engage with

the Barrel thread already cut.

The oversize start permits a thread to be

established and then by trimming the thread tips away, there is enough for the

Chaser to easily engage and re-cut the threads which will eventually reduce the

diameter to fit the female thread in the Breech Bore.

The oversize start permits a thread to be

established and then by trimming the thread tips away, there is enough for the

Chaser to easily engage and re-cut the threads which will eventually reduce the

diameter to fit the female thread in the Breech Bore.

Similar to the previous Thread Chaser preparations, you will need to use the

Parting Tool to slightly lower the level at the front of the spigot and at where

the spigot meets the bulk of the cylinder, in order that the Chaser has room to

come away from the threads before it barged into the edge of the cylinder.

This time, the Chaser is lifted out of the threads by lowering its handle while

moving in the smooth circular motion.

With the lathe speed reduced, new threads were produced and checked against

those in the Breech Bore before being trimmed back parallel again and again until

eventually they fitted into each other. Bear in mind that the top of the threads you are creating

at this step, need to end up in the

bottom of the threads you left in the Barrel.

This time, Paul did need to

reinforce the threads by pouring very thin superglue onto them while keeping

the piece moving round in order to avoid pooling and allowing enough time for

the glue to be drawn into the pores and harden before attempting to re-thread.

Only 2 or 3 threads are needed for the Breech Cap to grip the Barrel so once the

threads were matched, the length of the spigot was trimmed back accordingly with a Parting Tool and the thread depths carefully cleaned up with

400 grit abrasives.

A centre mark was made on the end where a hole for the Rod to slide freely

through the entire Cap was drilled using the Jacob's Chuck. Paul planned to use

a 4mm dowel of Bamboo so this hole needed a 4.5mm drill bit. Finally, after

allowing enough for space for the curve of the Breech, the piece was parted off

square and the drilled through hole was sanded/polished to aid free movement.

Knob

The next component was the Knob for pulling with your fingers to compress the

spring. Being able to finger grip this component dictated how big to make

its diameter but once determined, this was a simple shape for a Spindle Gouge.

It then needed a 4mm hole to grip the Rod (this time not going all the way

through). The component was sanded as required, the end squared off with a Skew

before being parted off and the rest of the curve sanded back.

Piston

With a fresh blank in the o'Donnell jaws and callipers set to 17mm

(for a smooth travel within the 18mm Breech Bore) about 20mm length of cylinder

was gradually turned to 17mm diameter using the callipers as shown above.

As Paul was considering using a trigger to release the compressed spring, he

fashioned the Piston as shown in the first photo.

The Barrel was presented to the component on the lathe to check for fit before

the 4mm drill in the Jacob's Chuck drilled a hole of at least 10mm for the Rod

to be eventually glued in; Paul had considered to drill completely through

because this component wouldn't be visible and a hole would allow glue to be

applied to the end of the Rod. The piece was sanded and parted off.

Shaping the Barrel

Prior to final assembly of the firing mechanism, the Breech Cap was screwed into

the Barrel and then mounted between a Light Pull Drive Centre and a Tail Centre

making use of the drilled holes at each end. A Spindle Roughing Gouge was used

to create a pleasing shape. The curve of the Breech was formed to the shape as

shown in the first photo and the piece was sanded through the grits as

necessary. Any additional decoration could now be applied as desired.

Assembling

After one end of the Rod had been glued into the Piston, its precise length

could now be determined by assembling the Spring and the Breech Cap, screwing

the Cap into the Barrel and while feeling the Piston against the 8mm Bore, mark/cut the extended Rod at whatever was the depth

of the drilled hole in the Knob. It's probably more sensible to remove the

firing mechanism from the Barrel so the Cap can be held against the Spring while

the Knob & Rod are glued in order to avoid any surplus gumming up the Cap.

Rules for this Competition :-

● The piece will be judged on it's aesthetic appearance;

● It must be capable of propelling the provided pencil;

● The Club will provide 8mm hexagonal pencils with a rubber one end &

blunt the other;

● Powered by Spring/Elastic/Bungee/Compressed Air etc; (Chemical reactions

prohibited!)

● No restriction on size of Shooter.

● The Shoot-Off will be an entirely separate Target Competition from

a table top and its

Rules will be explained on the Night.

The January 2025 Competition was set to create a Pencil Shooter(s) of predominantly turned components that can propel a pencil.

(photos by Andy Ogilvie, Rick Patrick & Paul Reeves)