Martin Saban-Smith

Demonstration of Proportional Design

& Finishing Techniques

at MWCC Club Night on Thursday, 18th April 2024

Based in Four Marks, East Hampshire, Martin has been an ardent wood turner for

ten years and on the Register of Professional Turners since the last seven.

In 2015 he produced a range of waxes, oils, sealer and lacquers under the name

of Hampshire Sheen followed by blending his own range of water based colour dyes in

groups of shades that compliment each other - the Intrinsic Colour Collection.

He has expanded his online presence by presenting online free and paid-for

demonstrations via his YouTube channel and through Zoom and founded

‘Woodturning360’ - a solely online turning club that features monthly

demonstrations of professional turners from around the world.

Leaving Social Media behind, tonight will be his first 'on the road'

demonstration for quite some time.

From a background of photography, Martin's emphasis on turning appears more

artistic than practical, but he always explained his reasons for the creative

skills he was about to do next during his demonstration of turning & finishing

together with the mathematics he used to produce such a pleasingly proportioned

finished composition.

As a photographer and a graphic designer in previous years, he was well used to

the composition principle known as 'Rule of Thirds' but for some time now, he

has been turning bowls using a similar but different rule; "The Golden

Ratio" which appears in countless places in nature and is used extensively

in art, graphic design & architecture.

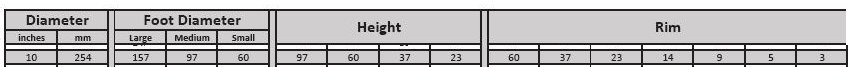

It is basically the number 1.618 which you use to divide your

largest dimension (diameter of a bowl/platter; height of hollow form) to provide

a natural proportion. Dividing only once might be wrong for the piece, so just

divide by the 1.618 again and again until it looks right while still preserving

this natural proportion. For example, by eye you might consider the foot

of a 10" (254mm) bowl seems fine at your optimum chuck diameter of 50mm but using the golden

ratio for a 250mm diameter bowl, guides you to a 60mm foot (because the adjacent Golden

Ratio option of 97mm looked inappropriate).

courtesy of Martin Saban-Smith

TURNING

With a 10" by 3" Ash bowl blank held between a screw chuck and live tail centre

ready to turn on the lathe, Martin stopped to remove his watch and health

monitors from his left wrist and put them on his right wrist. He is naturally

left-handed but for turning, even in cold conditions, he keeps his left hand and

forearm completely bare to remove any possibility of anything that could snag

and drag him into danger. At home, he wears a full face shield but for the

sake of being audible tonight, has compromised by wearing all-round safety

glasses.

Martin had selected his standard Sorby bowl gouge with a

50º bevel, which he finds less aggressive than smaller angled bevels. He

discussed his 'Three Points of Contact' control of the gouge comprising of

toolrest, right hand & body. Because he is left-handed, Martin finds a

pull cut comes naturally for him to control the tip of the gouge and commented that push cuts can so easily end

up diving into the wood involuntarily. With the gouge handle down low on

his thigh and an open flute, he tidied up the edge of the blank before finishing

off with a careful push stroke once it was trued all round.

The centre of the face was squared off and dividers used to mark out the spigot

required for his One Way gripper jaws. He used a ½" spindle gouge to

square off the corners of an 8mm spigot and quickly removed the waste.

Next came the maths. As we knew the final diameter of the bowl, we needed to

work out the diameter of the foot; from there we could work out a proportional

height of the bowl and finally the thickness of the wall. So a 250mm

diameter bowl would look well with a 60mm foot; the 3" blank could only at best

accommodate a 60mm height (even though this leads to wasting 15mm from the

eventual top of the bowl blank); the final dimension to consider is the wall

thickness. From the table above, a rim size of 14mm seems unnecessarily too thick while 5mm

feels too thin for a piece of Ash, so 9mm would be the best plan. Thus nothing

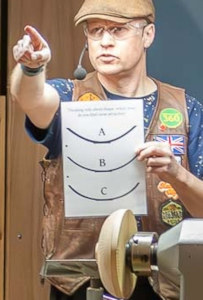

is left to be gauged by eye other than the shape of the curve. Martin

asked which of his 3 drawn curves we preferred. Eight engineering minded

of us chose curve A which resembles a suspended coil; another nine chose B

which is a perfect arc of a circle and 20 chose C which is a natural part of a

Fibonacci spiral. We then discussed if we were given a spectacular piece

of wood to turn, would we be more conscious of the final shape or for keeping as

much of this beautiful wood as possible. The consensus favoured shape, to which

Martin said, "Good! Then you won't mind me discarding 15mm off the top of

this piece of Ash in order to keep proportional shape."

From the table above, a rim size of 14mm seems unnecessarily too thick while 5mm

feels too thin for a piece of Ash, so 9mm would be the best plan. Thus nothing

is left to be gauged by eye other than the shape of the curve. Martin

asked which of his 3 drawn curves we preferred. Eight engineering minded

of us chose curve A which resembles a suspended coil; another nine chose B

which is a perfect arc of a circle and 20 chose C which is a natural part of a

Fibonacci spiral. We then discussed if we were given a spectacular piece

of wood to turn, would we be more conscious of the final shape or for keeping as

much of this beautiful wood as possible. The consensus favoured shape, to which

Martin said, "Good! Then you won't mind me discarding 15mm off the top of

this piece of Ash in order to keep proportional shape."

Although tonight's maths was starting with the largest factor (the bowl width)

and used to calculate down to the narrowest factor (bowl thickness) by dividing,

Martin emphasized that if, for example, you needed to provide a piece with a

specific foot size, then the 1.618 still works by multiplying to find a

proportionate bowl width and by dividing to find the appropriate wall thickness.

He drew a 60mm circle for the outer edge of the foot. Martin's preference is a

small coved edge to the side of the foot that feels comfortable to his finger

tips;

not so small to be thought an accident; not so big to look like a pedestal. Next, he drew a line around the rim 60mm up the side of the blank

from the bottom line of the foot. The final shape of the curve is visualised to

run from bottom centre of the foot, onwards beyond its outer edge and to

end up vertical by the rim's pencil mark. With this in mind, he

started just short of the foot line to leave about a 3mm step foot before

removing the bottom corner with his bowl gouge and working towards the Fibonacci

curve. He stopped regularly, took a step back to view and then felt the surface

in order to see where on the curve he needed to go slightly deeper with his next

cut.

FINISHING

The quickest way to finish is to leave the best tool finish you can before

resorting to abrasives. Martin favours a bowl sander with the lathe turning at

the same speed he finished with his gouge. While facing square to the rails, he

can keep the sander in contact by swinging his arms without twisting his back.

Contact is made at the 7:30 position (as viewed down the rails towards the head

stock) so he could see

the whole length of the sanding as he worked from foot to rim. Once again,

he stopped regularly to check for any tear-out patches that still needed work

before moving down the sanding disc grits. He admitted that he might use the coarser

grits more than once but will only use fresh abrasives for the finer grits.

Inward pressure is light enough to ensure the pad keeps rotating without

creating too much heat; particularly important for exotic or oily woods which

can readily check/crack (eg Yew) and is another reason to progress down the

sanding disc grits as soon as each has abraded the previous grit's scratches away. As

some finishing product was going to be applied, Martin tends to stop after 400

sanding grit because the smoother the surface, the harder for the product to grip/key

to.

After sanding, particles need to be cleared out of the grain, particularly with open

grain wood.

First choice for Martin would have been air jet (not available tonight); next

would be Liming Brush or otherwise by Methylated Spirits. He had a Libéron

Liming Brush with long stiff bronze bristles although he did warn against using

a 'suede cleaning' brush which despite having short copper/brass bristles, will

easily scratch and produce a wholly inferior result.

The choice of finishing type needs to consider which is most appropriate.

▪ Bright & Shiny ▪ Satin ▪ Flat ▪ Food Safe ▪ Scratch Resistant ▪

e.g. Big pieces aren't flattered with large reflective high gloss surfaces

but can be enhanced with a matt finish.

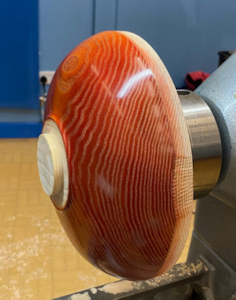

The outside of this Ash bowl didn't have a lot of figure so would benefit with

some co-ordinated colour. We are not trying to hide the wood so a dye

would be preferable to a stain.

♦ a DYE is colour designed to penetrate,

♦ a STAIN is diluted paint that lies on the surface.

Dyes can be either 'spirit' or 'water' based and Martin asked us to select one

of his water based wood dye ranges - Tonight we chose 'Fiery Sunset'.

As

dyes & stains imply, disposable gloves are essential. Martin uses water

based dyes because they are slower to dry than spirit and therefore one has more

time when applying by hand. He could have applied with an airbrush but

tonight he used a folded kitchen roll with a couple of splashes of the first

colour (Ruby) which he dabbed with little or no pressure in patches before, most

importantly, feathering the colour out at the edges. The wood naturally

draws in the dye so it's important not to apply it heavily or else some areas

won't be able to absorb added colours. He used a new folded paper towel for the

next colour (Burnt Orange) in a clear area ending again with feathering out at

the edges, either leaving gaps or else working into the previous feathered

edges. A third colour (Flame) was applied as before. After a short rest,

he used a clean paper towel with the lathe turning to dry off the surface.

With the lathe stopped, second coats of the same colours were applied more or

less in the same places, this time feathering in all the gaps although the

second coats wouldn't penetrate as much as the previous coat underneath. After

further time and drying off with a clean paper towel again, the lathe was

stopped, the long grain surfaces were identified and subsequently hand sanded

back with the same disc grit that had been used last when sanding (i.e. 400 grit in

our case). The Liming Brush was used again before the long grains were

dabbed and feathered as before with the paler Honey colour.

As

dyes & stains imply, disposable gloves are essential. Martin uses water

based dyes because they are slower to dry than spirit and therefore one has more

time when applying by hand. He could have applied with an airbrush but

tonight he used a folded kitchen roll with a couple of splashes of the first

colour (Ruby) which he dabbed with little or no pressure in patches before, most

importantly, feathering the colour out at the edges. The wood naturally

draws in the dye so it's important not to apply it heavily or else some areas

won't be able to absorb added colours. He used a new folded paper towel for the

next colour (Burnt Orange) in a clear area ending again with feathering out at

the edges, either leaving gaps or else working into the previous feathered

edges. A third colour (Flame) was applied as before. After a short rest,

he used a clean paper towel with the lathe turning to dry off the surface.

With the lathe stopped, second coats of the same colours were applied more or

less in the same places, this time feathering in all the gaps although the

second coats wouldn't penetrate as much as the previous coat underneath. After

further time and drying off with a clean paper towel again, the lathe was

stopped, the long grain surfaces were identified and subsequently hand sanded

back with the same disc grit that had been used last when sanding (i.e. 400 grit in

our case). The Liming Brush was used again before the long grains were

dabbed and feathered as before with the paler Honey colour.

Before waxing and depending upon how

absorbent the wood, it might need to be Sanding Sealed to prevent the end grain

sucking in more embellishing wax colour than could be absorbed into the long grain. Box

Wood and Yew might not need any or at least only a single coat; open grained

wood like Ash is likely to need at least one coat of sealer. Of the three types

of Sanding Sealer, Martin finds Shellac too sticky, Acrylic dries too slowly

leaving Cellulose as the best option. Whichever you use, Martin warned

that it must be applied quickly and evenly to avoid rippled 'tide marks'

spoiling the effect of any added embellishing wax used to enhance the grain as

he had planned for this piece of Ash. We had the choice of black, bronze (brilliant for Sepele, Walnut) or gold. These Embellishing Waxes worked like gilt creams but

don't need 24 hours to set. Instead, they include Carnauba and Micro-Crystalline

waxes plus a pigment, which if applied frugally, will be set within half an

hour. The consensus was for gold.

Martin decided to add a very thin final coat of Microcrystalline Wax

buffed up to a shiny chatoyant finish. When buffing, he warned that it was

important to use no more than a light finger pressure or else the frictional

heat will melt onto the buffer and you won't get the smooth deep gloss finish

you wanted.

The piece was then mounted onto the prepared spigot and the top 15mm or so waste

wood above the pre-marked height line was quickly nibbled away with pull cuts.

The Golden Ratio planned Rim thickness was 9mm which was pencilled in. Trying

to cut Ash accurately at this thickness does need to be done in stages so that

the wood below supports your final inside cut without letting the wood vibrate

and spoil the cut. Starting near the centre, Martin turned away about a

3cm bowl shape depth and

worked his way out towards the pencil line. Once close to the thickness

mark, he used the bevel to parallel the outside edge down to this first cleared

depth before stopping to look and feel the inside. This had to be right before

moving onto the next 3 or 4cm hollowing out.

He preferred to make every cut as a finishing

cut, because it gives one muscle memory practice for the final pass. He

was happy to leave a cone in the centre as this added structural strength to

supporting the upper sides and could be easily turned away later.

Having taken care in keeping the inside wall smooth across all the stages and

parallel to the outside and with any centre cone turned away, the final

hollowing cuts were a sweep with the handle starting from down and ending higher

as the gouge tip was guided to the centre with its bevel ending up parallel to

the bowl's rim. With the lathe turning, the inside surface was sanded with a

small round pad powered by a drill making contact at about the 4 o'clock

position (as viewed down the rails).

Lack of time didn't allow for the piece to have the inside treated with numerous

coats of finishing oil (some of which require 24 hours after final application) nor to be held in Cole Jaws and the tenon

removed but Martin finished tonight's piece with his powered abrasive pad to

create a small bevel to remove the sharp edge of the bowl's rim. This feature

also outlined and enhanced the decoration.

Martin highlighted that oils that dry (eg Danish Oil) are far more durable than

waxes with regard to anything hard, sharp or moist being put into a bowl.

(photos by Vic Russell, Andy Ogilvie &

Natalja Saban-Smith)

<to

Pro Index>

Martin Saban-Smith is a Registered Professional Turner (RPT).

He can be found at

<www.hampshiresheen.com>

Facebook: <www.facebook.com/msabansmith>

YouTube: <www.youtube.com/c/msabansmithwoodturning>